There is something very calming about spending time with honeybees. Their world moves at a slower speed – it’s as complex, dangerous and brutal as our own, but their lives are simpler and more measured in their pace. To sit by the hive-entrance is to catch a glimpse of their experience – sharing a physical space with the super-organism of the colony. And however overwhelming the human world may feel, a return to my garden-hive offers a constant source of peace and calmness, meditation and solace.

I had a similar feeling when I visited the ‘Hive’ sculpture in Kew Gardens last autumn. It’s a house-sized metal frame, wired up to a beehive. Sensors inside the beehive capture the vibrations of the bees, and these signals are translated into light-sequences and musical-sounds. Standing inside the sculpture felt similar to entering a hive – not in terms of the physical space or literal experience of being a bee, but on an emotional level it felt as if it captured something of the emotion. Instead of watching bees, the viewer watches the other people: working, communicating, sensing, giving directions, raising their young, and pointing at the sun.

I had a similar feeling when I visited the ‘Hive’ sculpture in Kew Gardens last autumn. It’s a house-sized metal frame, wired up to a beehive. Sensors inside the beehive capture the vibrations of the bees, and these signals are translated into light-sequences and musical-sounds. Standing inside the sculpture felt similar to entering a hive – not in terms of the physical space or literal experience of being a bee, but on an emotional level it felt as if it captured something of the emotion. Instead of watching bees, the viewer watches the other people: working, communicating, sensing, giving directions, raising their young, and pointing at the sun.

Wolfgang Buttress, the artist who designed the ‘Hive’ sculpture at Kew is part of the ‘BE Collective‘, a group of musicians who perform music based on the sounds of the hive. Sensors inside a beehive capture the bee-sounds, and the musicians play alongside these noises, part-improvising in the same key as the bees. When I read that there was a one-off live-performance in Coventry Cathedral, I bought a ticket immediately. The performance was part of ‘Scratch the Surface‘, a two-week mental-health arts festival.

I arrived early.

“It’s not ready yet – they’re still setting up the magic,” said the woman at the ticket-desk. I could see a gauze screen hung across the cathedral. Projected onto it were coloured arrows and the word ‘test’ in big letters. Behind that, half-hidden, musicians tuned their instruments. I went outside, to wait for the magic to be prepared.

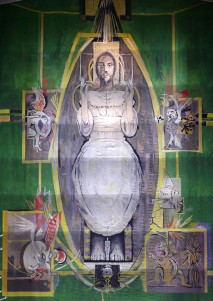

I sat on the steps of the old cathedral, and watched the reflection of the falling dusk. I could see through the windows of the new cathedral. The ‘test’ graphic had gone now, replaced with a moving-image of golden pollen, windblown like falling snow. Above the screen there was an image of large white figure. Through the glass, it looked like a hybrid of bee and human – the curve of the knees like a fat abdomen, the fabric of the sleeves marking the narrow edges of the thorax, and background lines suggesting three walls of a honeycomb cell. It was pure-white, like bee-brood: cocooned, and safe: half-human half-bee.

I sat on the steps of the old cathedral, and watched the reflection of the falling dusk. I could see through the windows of the new cathedral. The ‘test’ graphic had gone now, replaced with a moving-image of golden pollen, windblown like falling snow. Above the screen there was an image of large white figure. Through the glass, it looked like a hybrid of bee and human – the curve of the knees like a fat abdomen, the fabric of the sleeves marking the narrow edges of the thorax, and background lines suggesting three walls of a honeycomb cell. It was pure-white, like bee-brood: cocooned, and safe: half-human half-bee.

Other people were waiting on the cathedral steps, and I asked about the figure – was it part of the show? Was it meant to be a bee?

“It’s part at the cathedral,” they said, “it’s been there since the sixties. It’s the biggest tapestry in the world, or one of the biggest. It’s called Christ in Glory.”

To me it was still half-bee: Chrysalis Christ, Cocooned Christ, with the edge of a halo a suggestion of half-formed, folded wings. In the space between His feet was the outline of a sting. Perhaps I had spent too long with bees.

The magic was soon ready, and we took our places in the cathedral chairs. There were introductions – we were told that the beehive was on a local rooftop, and its vibrational signals were being transmitted down into the sound-mix. Dr Martin Bencsik, a physicist at Nottingham Trent University played a recording of one bee on the sensor. He spoke briefly about how the bees communicate with vibrations, and raised questions of language – whether the “meaning” of a message is determined by the sender or the receiver. It is up to the listener, he concluded, to understand any message that the bees might be sending. I thought about the tapestry above the altar – the artist may not have intended a bee, but that was what I perceived.

“I’ll be the queen, hand me my crown…“. The music began. Low cello-notes, an accordion, violin, guitars, and occasional vocals. The lead vocalist was excellent: a few simple phrases, sung powerfully. There was a beautiful clanging electric guitar. These were not songs with tunes that stick in the mind, but an ambient, atmospheric soundscape, echoing between the cathedral’s pillars.

It also seemed ambiguous too as to how much of the sound came from the live bees. At one point they built to a crescendo – volume increasing until the sound of the bees filled the cathedral. But it was difficult to tell if that was any different from other performances – I could not hear anything beyond the background frequency of the hive, and wondered if it sounded any different from any other beehive at night. The bees were not aware of the music being played, not aware that they were being listened to. Aside from the novelty, I do not think the experience would have been any different with prerecorded bee-vibrations.

The images projected onto the screen were impressive – bees being poured into a cello, closeups from an observation hive, some shots of the ‘Hive’ sculpture, and circular, mandala-like designs of bees and lights. I had to suppress the questions from my inner beekeeper: what are the bees doing there? why is that bee moving like that? in which year was that queen born? There was no narrative to the pictures, but the projection matched well with the dreamlike soundscape.

The images projected onto the screen were impressive – bees being poured into a cello, closeups from an observation hive, some shots of the ‘Hive’ sculpture, and circular, mandala-like designs of bees and lights. I had to suppress the questions from my inner beekeeper: what are the bees doing there? why is that bee moving like that? in which year was that queen born? There was no narrative to the pictures, but the projection matched well with the dreamlike soundscape.

The live-ness of the images was left deliberately ambiguous. I wanted to believe that it was (at least in part) live footage of the rooftop bees, but it seemed too neat, too well-produced. Perhaps the endoscope-footage could have been spliced in, but I suspect the whole visual-feed was pre-recorded. But that did not lessen the magic.

The finale, ‘Blue Lullaby’ was beautiful – I had heard a recording a few days before, but the live version was so much more powerful. It was music that makes you forget where you are: beside a beehive, or inside a beehive, or an abstract consciousness, lost somewhere in experience and melancholy beauty – it conjured a late-autumnal world of honey-caps, ivy pollen and bee-flight. I was reawakened to the strength of the bees, the soaring expanse of their experience. When the lights came up, I left the cathedral utterly enthralled to the wonder of them.

The finale, ‘Blue Lullaby’ was beautiful – I had heard a recording a few days before, but the live version was so much more powerful. It was music that makes you forget where you are: beside a beehive, or inside a beehive, or an abstract consciousness, lost somewhere in experience and melancholy beauty – it conjured a late-autumnal world of honey-caps, ivy pollen and bee-flight. I was reawakened to the strength of the bees, the soaring expanse of their experience. When the lights came up, I left the cathedral utterly enthralled to the wonder of them.

===

© Jack Pritchard, Oxford, October 2017.

pritchard237@gmail.com

One thought on “Review of BE, Coventry Cathedral, 2017”